Ruin Arrangements

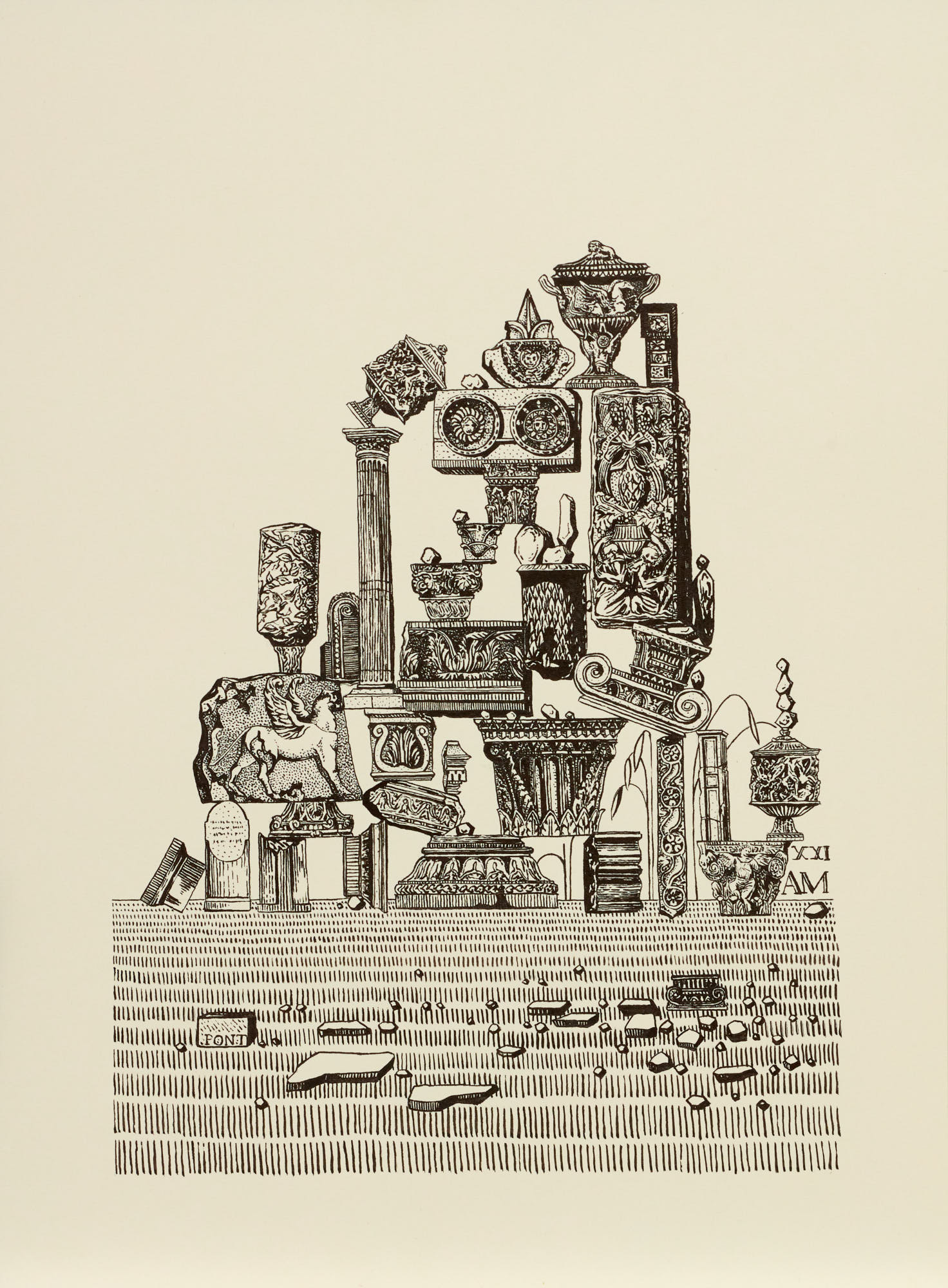

Image: Anouk Mercier, Stacked VII, 2021, Ink on Paper, 28 x 38cm. Photo: Max McClure

Commissioned text to accompany a forthcoming exhibition of Anouk Mercier’s Ruin Arrangements drawings. The writing takes the form of a series of numbered fragments, reflecting the structure of the drawings themselves.

“Cultural heritage does not exist, it is made.” – Regina Bendix

I

You can’t walk far along the modern streets of Nîmes before you’ll turn a corner and find a street or square in a state of mid-excavation. At the bottom of muddy trenches you might see the outline of Roman foundations, or fragments of mosaic, plaster and pottery. Artist Anouk Mercier’s love of ruins began here, during childhood summers visiting her grandmother. The most significant Roman town in France is a new city built directly on top of an ancient one. When a road is dug up, ruins inevitably appear from beneath, the past continually resurfacing.

Such finds are so frequent that many artefacts stay in the ground after archaeologists have recorded them. The most historically important objects are preserved or placed on a museum plinth. The rest is covered back over with rubble and smoothed with stinking bitumen. This surface will decay in time too and eventually be hidden beneath another new layer of urban strata.

II

Mercier’s Ruin Arrangements (2018-ongoing) is a series of black ink drawings of stacked, piled and balanced architectural fragments. Each composition is a collage of elements appropriated from Piranesi’s (1720-1778) etched fragments of Rome, which Mercier photocopies and cuts out, then selects at random to draw one at a time: a lucky dip of statues, pilasters, cornices, architraves and finials.

Densely patterned vases balance on top of scrolled capitals. Ornately carved pedestals are propped against fractured friezes. A griffin perches beside a cherub. Figures emerge between swirling vines and acanthus leaves: the jolly moustached face of a god or giant; a pair of cheeky nude bums; a frowning face with a dark O for a mouth; an angel with outstretched wings; a robed couple reaching towards each other across a spewing fountain. Incomplete Latin words hammered into stone: MENTO; BIBVLO; ABITRATV. Pegasus strides across an urn.

Within the series the Pile O’ Ruins drawings are dense heaps of these Roman artefacts. Columns protrude from the rubble at jaunty angles, stiff and comically defiant (or perhaps delusional) in their still-more-or-less-uprightness. Elsewhere wooden props provide extra support to particularly precarious objects.

The Stacked drawings are more orderly and even more absurd. These fragments are meticulously assembled: counter-balanced, propped, buttressed in neat arrangements. Rocks and pebbles of just the right size are wedged between decorative fragments, or balanced in small towers like the tip of a cairn on a hilltop. The sense of process, of building these drawn asymmetric structures bit by bit, is tangible. Like a child playing with building blocks, the aim is to achieve balance. Mercier’s monuments appear just about stable; but collapse is always possible.

III

In the 18th century, aristocratic young men across Europe commissioned follies for the landscaped gardens of their stately homes, inspired by the Greek and Roman temples, bridges and statues they had seen on their Grand Tours. These objects signalled wealth, education and taste, and the desire that the British Empire be associated with that of ancient Rome via its grand antiquities.

The Romantic craze – a ‘ruin lust’ – for the aesthetics of picturesque decay and decline led some landowners to construct artificial ruins or partially destroy existing buildings for decadent and dramatic effect. Others shipped ancient stone from abroad to be remade as crumbling objects of imperial fantasy: columns stripped from Leptis Magna in Libya (a site plundered in the previous century by Louis XIV for use in his palaces at Versailles and Paris) were reassembled beside Virginia Water, a man-made lake in the royal grounds of Great Windsor Park in Surrey.

IV

The piles of Roman rubble in Ruin Arrangements evoke more recent histories too. The looting and destruction of Palmyra, razed with explosives and bulldozers; a war against cultural heritage as well as people. And that ruin which haunted the beginning of the 21st century: the jagged, smoking remains of New York’s World Trade Center on 9/11. In a photograph taken two days after the attacks, triangular steel shards jut into a blue sky, above the surviving arched entrance of one of the Twin Towers: a contemporary version of an architecture – and its ruins – found across continents and centuries.

V

An April 2021 New York Times article reported that displaced Syrians are seeking refuge in the ruins of ancient villages in the country’s northwest. Photographs show the remains of Deir Amman, a Byzantine settlement abandoned 1000 years ago. Among the huge slabs of sculpted stone and semi-collapsed walls are modern canvas tents and improvised shelters made from tarps and blankets. Some families have used the weathered pre-cut stone to build new structures and animal pens – repurposing antiquity to deal with the real and immediate problems of the present.

VI

Europe’s great ruins continue to hold a romantic allure. Tourists flock to the Acropolis and Colosseum to admire these imposing architectural feats of empire (built by slave labour), which represent notions of continuity and permanence: after we are all gone these stones will still stand. In Mercier’s drawings tufts of grass and weeds sprout in the gaps along the base of the stone structures. As with all ruins, nature finds its way back. All empires eventually crumble and fall.

The value of ruins is hierarchical and often clearly demarcated. A significant site has a wall or fence placed around it, a sign is erected to explain its importance. Local cafés borrow its name, gift shops print its image on fridge magnets and tea towels. You pay an entrance fee, buy the guidebook, take home photographs that don’t do it justice.

A ruin must be preserved in its current state or risk deterioration from the picturesque to a pile of debris. But how much harder it is to take them seriously, to be overawed by their illusion of power and authority, when they are braced with scaffolding or sheathed in semi-transparent fabric – a futile disguise for the conservation work beneath. The romantic spell is swiftly broken.

VII

Ruin Arrangements articulate an attempt to find stability among ruin. Who would construct these stacked monuments that appear ordered but could come crashing down at any moment? An ousted ruler? An optimist? A comedian? An historian? A new mother? Mercier’s structures are hopeful, absurd, delusional, clinging on, keeping going, preserving, trying to maintain control, defying the inevitability of gravity.

These are not nostalgic reconstructions of a past that no longer exists, but remixes: a fantastical new architecture which understands that ruins, like history, are dynamic and entangled with the present. Just as Piranesi created images of Rome that mixed architectural reality with invention, Mercier playfully reassembles the past to suggest that there are alternatives to the cemented historical narratives that have been dominant for so long.

Her drawings reflect an uncertain present in which many of the structures, systems and institutions that have previously seemed unbreakable appear to be precarious. Amid political upheaval, social division, global pandemic and impending climate catastrophe, Ruin Arrangements ask what future will be laid over the ruins of the present, and act as a reminder that the most human of work is in the search for balance.

Regina Bendix quoted in Historical Documents of the Irish Avant-Garde, ed. Jennifer Walshe.

‘Fleeing a Modern War, Syrians Seek Refuge in Ancient Ruins’, New York Times, 20 April 2021.